Phantom in the Sky: USMC Aviator Terry Thorsen's Life-Changing Lessons in Perseverance

Terry L. Thorsen’s Phantom in the Sky Imparts Lessons on Perseverance

Terry L. Thorsen was an unlikely candidate to be cutting through the skies in the formidable F-4J Phantom II. Persistent bouts of airsickness nearly forced him to wash out of aviation training, and made subsequent flights in the fighter jet physically and emotionally draining. Despite detractors who doubted his fitness, Thorsen ultimately proved the quality of his mettle, performing 123 combat missions and earning 10 air medals, two Navy Unit Commendations, and a Bronze Star while deployed to Vietnam between March and August 1969.

As with other large fighter jets, operating the F-4 was a two-man job. A pilot in the front seat kept the plane airborne and dispensed live ordnance, while a radar intercept officer, or RIO, like Thorsen took charge of communications, navigation, and locating and intercepting enemy aircraft from the back seat.

Two VMFA-232 Phantoms flying out from Marine Corps Air Station El Toro, in Calif. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

When he published the autobiographical Phantom in the Sky: A Marine’s Back Seat View of the Vietnam War in March 2019, Thorsen became the first Marine F-4 RIO to write from the perspective of the “guy in back.”

From his home in Mansfield, Texas, Thorsen recently spoke with the Freedom Hill Press about the process of writing Phantom in the Sky, and how his faith and the lessons of his Marine Corps training helped him to persevere through hardship throughout his life.

Telling his Story

Thorsen knew he would record his story from the moment he left the Marine Corps, but getting it down took some doing. Phantom in the Sky was published just weeks shy of the 50th anniversary of Thorsen’s first combat mission, on April 1, 1969. It was the product of 30 years of writing, editing, and refusing to give up.

First, Thorsen began assembling his flight logs and schedules, letters home to his family, aviation manuals, and photographs. Next, he “just started roughing out [the story],” and “within 20 years, [he] had the beginnings” of Phantom in the Sky. He “threw himself into the book” during a short period working in Tacoma, Wash., but ultimately had to wait until he retired to finish the job. After two years “writing in five-subject spiral notebooks” he reports that “it just kind of took shape slowly.”

Thorsen is adamant there would be no Phantom in the Sky without the help of his current wife, Audrina, to whom the book is dedicated. He admits he “was ready to give up several times,” because the story was “repetitious and verbose” at a whopping 157,000 words. His efforts to find an agent or a publishing house bore no fruit until Thorsen found a professor at the University of North Texas’ North Texas Military History Center who was willing to give him a chance.

The manuscript still required a significant edit, which took Thorsen another two years to accomplish. While he cut “over 30 percent” of the book, Audrina “was right with [him]…She was [his] editor, she is [his] wingman.”

Phantom in the Sky

Thorsen’s decades of hard labor, and Audrina’s support, paid off. Phantom in the Sky is a tight, blow-by-blow accounting of his military career, heavy with unflinching personal details and social observations that document the Zeitgeist of the era.

Phantom in the Sky opens with Thorsen’s recollection of his decision to pursue flight training rather than wait to be drafted as the Vietnam War roiled. The decision rankled his first wife, but Thorsen knew he would prefer being in the air to being on the ground. (Phantom in the Sky is also dedicated to those ground forces who met the enemy face-to-face, “especially…those whose encounter became their destiny.”)

While heading to Quantico, Va. for Marine Corps Officer Candidates School, Thorsen recognized the heft of his choice. “I was now one of those [the protesters were] protesting against,” he writes.

The training schedule at Quantico was grueling, but devoid of modern-day political correctness. Thorsen recalls how monotonous slide decks were peppered with the occasional nude photograph to discourage officer candidates from falling asleep.

As Thorsen brings readers along to Basic Naval Aviation Orientation in Pensacola, Fla., he masterfully breaks down the world of aviation so that civilians, ground pounders, and aviators alike can understand and appreciate his stories of service. In Pensacola, airsickness threatened to make Thorsen “revert back to a ground officer,” while his marriage showed signs of strain.

After getting his wings, Thorsen was assigned to VMFA-232, the Red Devil squadron, in Marine Corps Air Station El Toro, in Calif., in March 1968. He describes his first flight in the Phantom as “euphoric,” explaining it continued to be “awesome…even after it became routine.” Airsickness, however, continued at El Toro. So did Thorsen’s marital struggles, as he realized he and his wife were “on the same journey, just not on the same page.”

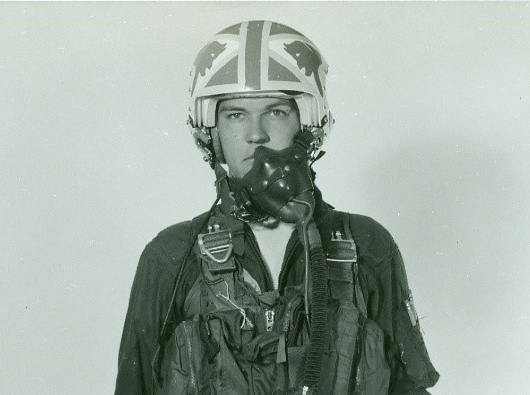

Thorsen in full flight gear, ready for a hop in the Phantom with the VMFA-232 Red Devil squadron. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

An F-4 flying low over the Calif. Chocolate Mountain Range after an ordnance drop. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

Flying soon became “mostly routine with interruptions of sheer terror,” as Thorsen faced the reality that “flight pay was hazardous duty pay.” Undergoing several near-death experiences made the RIO exceptionally skilled in handling abnormal events. Some aviators Thorsen recalls were not as lucky.

Thorsen snapped this photo of two VMFA-232 F-4s waiting to perform a retirement ceremony flyover. Fifteen minutes later, his own Phantom nearly crashed. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

Thorsen remains in the Phantom while pilot (right) and a Staff NCO (left) examine the left engine intake. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

VMFA-232 Phantoms refueling while en route to Hawaii. From Hawaii, they would continue on to Vietnam. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

The Red Devils “were flying into Hell by way of Heaven” as they crossed the Pacific headed for Chu Lai, Vietnam in March 1969. Thorsen describes being broken in to his new surroundings with rocket attacks and Hanoi Hannah’s radio information operations on the first night in his Southeast Asia hut. For the next five months, Thorsen flew multiple missions nearly every day, often taking shifts on the “hot pad” to provide quick response support to ground forces.

Thorsen recalls dropping ordnance in close air support missions over locations familiar to Vietnam War buffs, including Khe Sanh, the A Shau Valley, the Hoi An River basin, Quang Tri City, and Dong Ap Bia, better known as “Hamburger Hill.” He also targeted anti-aircraft artillery and surface-to-air missile sites, and once acted as an escort for a B-52 conducting a bombing raid as part of Operation Arc Light.

The author in the Phantom on the flight line in Chu Lai, Vietnam. Courtesy of Terry L. Thorsen.

While deployed, Thorsen struggled with bouts of depression, and relied heavily on his faith in God to pull through those dark times. Letters home show that he mostly shielded his family from the truth about the enemy he was facing, and his feelings. With the exception of a happy interlude for R&R in Hawaii with his wife, Thorsen’s imperiled marriage did not benefit from his deployment.

Thorsen’s flights were sometimes harrowing, but Vietnam proved deadly for many aviators he knew, and life-changing for others. Berger, a pilot in Thorsen’s squadron, “refused to fly any more combat missions” after a difficult close air support flight. Afterward, he “flew the mail plane…[and] ultimately…was killed when his plane impacted a hill near…base while dropping flares at night.”

In another incident, Ewing, a helicopter pilot Thorsen met in training in Pensacola, had a terrifying experience with his Huey gunship.

“Ewing’s chopper took enemy fire. His co-pilot was killed and the helicopter sustained so many hits that it crashed right there, inverted. Both Ewing’s wrists were broken and he couldn’t undo his shoulder harnesses or his lap belt. He hung in his seat watching the enemy advance. The Recon team repelled the enemy with Huey Cobra air support, saving the day and Ewing…[Ewing] turned in his wings and returned to the States.”

In June 1969, Thorsen was reassigned to VMFA-334 after losing track of a classified piece of equipment. Embarrassed and insulted, he “went into a slump for a little while,” but continued flying perilous missions to support troops on the ground and attack enemy weaponry.

In August, Thorsen’s squadron left Vietnam for Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni, Japan. For the remainder of his deployment, he immersed himself in Japanese culture, which included accidentally taking a weekend trip to a Japanese brothel with his first wife and several other aviators and their spouses.

On his return to the U.S. in March 1970, rather than receiving a warrior’s welcome, Thorsen and his fellow service members were “searched…by sniffer dogs.” He came to recognize that “the only people Vietnam veteran status meant anything to were the veterans’ families and the military, and in reality, military-wise, only for promotional purposes.”

By the time he left the Marine Corps in September 1970, Thorsen reports that his service had given him a new perspective on the cost of freedom, and the importance of American military superiority.

Remember your Training

Phantom in the Sky will be an engrossing read for Vietnam veterans, and anyone interested in Vietnam War or aviation history. It also holds valuable lessons for modern service members and veterans.

The similarities between our current lengthy expedition to Afghanistan, in which we still have no defined end state to determine “success,” and the American experience in Vietnam are particularly striking. While post-9/11 service members are not subject to the same level of hatred Vietnam era service members faced (Thorsen himself was called a “baby killer” by a bank teller), the apathy of a civilian populace that has very little understanding of our current wars can be isolating.

Phantom in the Sky holds great value in that it allows readers to bear witness to Thorsen’s determination to succeed throughout a host of setbacks and difficulties, an attribute he emphatically links to his Marine Corps training. Thorsen writes:

“Once home…I went to my previous employer and demanded they give me my job back. Reluctantly they did. I hated it. No wonder, I was not yet twenty-seven years old, had flown twice the speed of sound and had seen the curvature of the earth from 52,000 feet. I had been in charge of Marine personnel, was a combat veteran having flown 123 combat missions, and been halfway around the world. I thought, what compares to that. After three months back in Texas, I procured a small business loan and bought a photography studio. This became my career for the next twenty years, using my acquired skills to manage personnel and my confidence to accomplish absolutely anything. Yes, the Marine Corps builds men; I was living proof.”

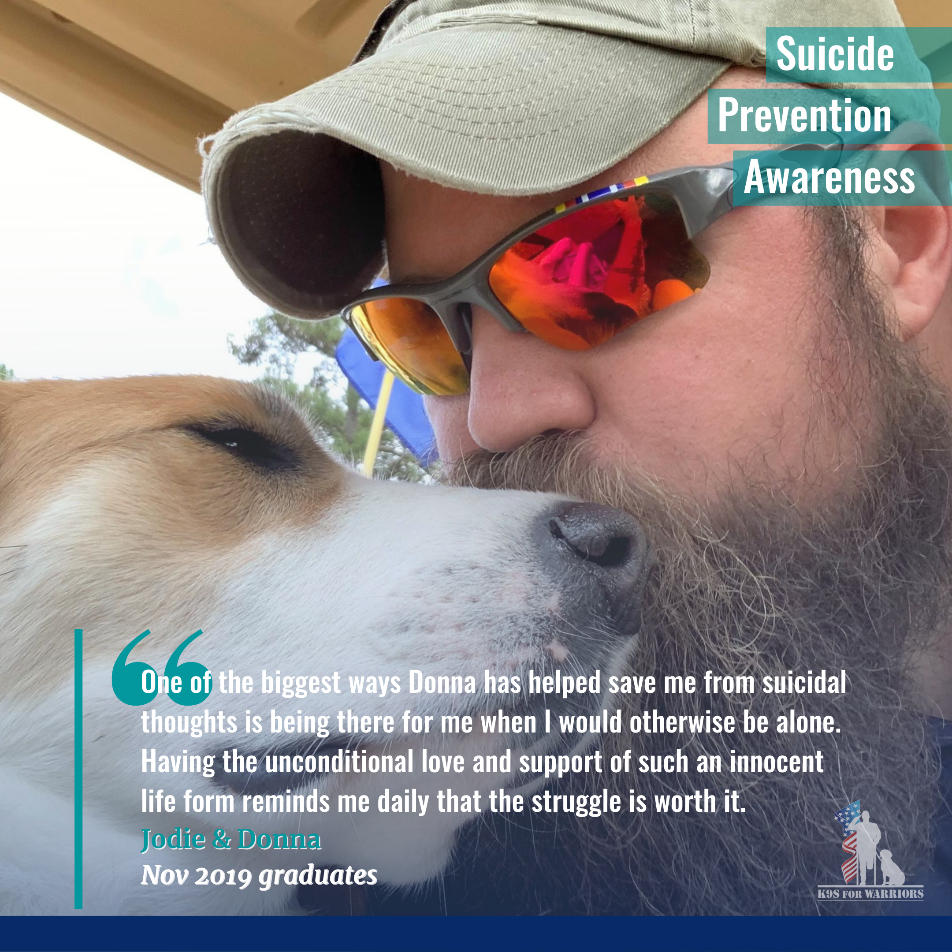

Though he “would hope that anyone, veteran or otherwise, would not get to the point where they just don’t feel like they have any reason to live, or that ‘I’m a burden to someone else’ or ‘I just can’t take it anymore,’” Thorsen knows this can be a reality for some warriors. He urges them to remember, “You’ve been trained, you were good at what you did, you had a force that you were part of and you had a direction.” After leaving the military, “you have to reassess your life, make some goals, and go for it. Nothing happens without making it a goal.”

Thorsen’s story is proof that simple perseverance, ingrained in every warrior during his or her military training, cannot be undervalued as a tool for overcoming setbacks and achieving success.

Want to be published in the Freedom Hill Press? Send us a pitch or a completed piece (under 2,000 words, please) to info@freedomhillcoffee.com. We can't wait to hear from you.