Veterans’ Service Continues After Conflict – The Story of the D.C. War Memorial

Between 1917 and 1918, 4.7 million Americans fought in the First World War. 116,516 gave their lives in the conflict. Around 204,000 veterans returned home with wounds, and possibly as many as one in five suffered varying degrees of “shell shock.” Others came back to the U.S. to encounter violent racism, experience perpetual unemployment, or find their farmland in disarray.

In the aftermath of the devastating war, the citizens of Washington, D.C., like Americans across the country, erected a local monument to their veterans and their beloved war dead. The District of Columbia War Memorial was designed by World War I veterans, who imagined the marble bandstand as a place where Americans could gather to celebrate and honor the District residents who fought in her name.

The District of Columbia War Memorial. Monday, April 13, 2015. Washington, D.C. (flickr/russellstreet)

Over the passing decades, the D.C. War Memorial fell into disrepair, until the last surviving World War I veteran led the charge to have the structure restored. Because of his efforts, the monument was returned to its former grandeur, preserving it for future generations of American civilians and veterans to unite in joyful memory of those honored souls who served a grateful nation.

On Veterans Day, we pay tribute to these and all American heroes, past and present, whose sacrifices unite us.

A Place to Gather and Remember

On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, an armistice silenced the guns of all countries fighting in the First World War. Just a month after the end of the conflict, the people of Washington, D.C. began a letter-writing campaign to advocate for a monument honoring the more than 26,000 District residents who fought honorably in what was then hopefully referred to as “the war to end all wars.”

In 1919, renowned D.C. architect and World War I veteran Frederick H. Brooke put forward a plan for a simple and classic circular, domed memorial made of white marble and surrounded by Doric columns. Meant to act as a bandstand, the memorial’s 44-foot diameter had sufficient space to accommodate the 80-piece Marine Corps Band. Each concert played at the memorial was intended to “be a tribute to those who served and sacrificed in [World War I.]”

Survey drawing of the D.C. War Memorial’s east and north elevations. n.d. Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/Boucher)

On June 7, 1924, Congress authorized the construction of the D.C. War Memorial. A memorial commission was created to plan its construction, and Brooke chose fellow veterans Horace W. Peaslee and Nathan C. Wyeth to help carry out his architectural design.

Fundraising commenced quickly, and involved participation from “street car and bus companies, two radio broadcasting companies, the motion picture theaters and vaudeville houses, hotels, banks, large stores, the Boy and Girl Scouts, the police and fire departments, and women’s clubs.” Even local schoolchildren took part in fundraising as “part of their education as future citizens of the nation.” Every child who raised five cents for the memorial fund received a special commemorative button.

After funds had been procured, the memorial commission chose a site for the structure on the National Mall in West Potomac Park, near Independence Avenue. A special committee assembled the names of the local residents who perished during the war. A local landscape architect approved the design for a grove of hardwoods, including elm, oak, beech, and tulip trees, which would surround the memorial to the east and west. A local construction company laid the foundation and built the structure with white marble quarried in Vermont. An eight-foot flagstone walkway was created around the monument, which was brightened with electrical lights.

On Sept. 30, 1931, the memorial was complete. Carved into its outer surface were the names of all 499 D.C. residents, including seven women, who lost their lives in the war. It was the first memorial of its kind to list all who died, “regardless of their race, class, or gender.”

A further inscription on the monument reads, “the names…are here inscribed as a perpetual record of their patriotic service to their country. Those who fell and those who survived have given to this and to future generations an example of high idealism, courageous sacrifice, and gallant achievement.”

A copper box in the memorial’s cornerstone contained the names of all 26,048 District residents “who answered the call of duty sounded by the war,” a November 1931 editorial from the Evening Star read. Here they would be “inclosed [sic] in the firm foundations, sealed against the ravages of age and decay.”

Survey drawing of the D.C. War Memorial. n.d. Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/Boucher)

The Memorial is Dedicated

The D.C. War Memorial was dedicated on Nov. 11, 1931, a date then officially designated as Armistice Day in honor of those who fought in World War I.

Present for the ceremonies were President Herbert Hoover, noted composer and conductor John Philip Sousa, and Gen. John J. Pershing, the famous commander of American Expeditionary Forces at the First World War’s Western Front. Numerous veterans and representatives from the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Disabled American Veterans, Gold Star Mothers, and American Legion were also in attendance.

Dedication ceremony for the D.C. War Memorial. Wednesday, Nov. 11, 1931. Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/Harris & Ewing)

At the dedication, 77-year-old Sousa, dressed in his Navy lieutenant commander’s uniform, led the Marine Corps Band in “The Stars and Stripes Forever.”

At exactly 11 A.M., Hoover gave the keynote address, explaining that “with each succeeding year, Armistice Day has come to be a day to pay tribute to the millions who valiantly bore arms in a worthy cause, and to renew resolves that the peace for which these men sacrificed themselves shall be maintained. However great our desire for peace,” he presciently continued, “We must not assume that the peace for which these men died has become assured to the world or that the obligations which they left to us, the living, have been discharged.”

The nation would soon discover that peace was, indeed, fleeting. Another 16 million Americans would fight overseas in the Second World War between 1941 and 1945. More than 1.7 million would fight in the Korean War between 1950 and 1953.

In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower would sign a bill that turned Armistice Day into Veterans Day. Henceforth, Americans would celebrate veterans of all wars on November 11.

A Memorial in Use, and Disrepair

The Marine Corps Band played to a crowd of 2,000 during the D.C. War Memorial’s inaugural use as a bandstand on June 2, 1932. Band leader Capt. Taylor Branson told the Evening Star that “Washington never before has had so ideal a place for our park concerts. The acoustics are all that could be desired and the setting is superb.”

By 1939, stains and crusting were accumulating on the memorial’s surfaces due to water leakage and maintenance struggles.

The final documented Marine Corps Band performance at the memorial occurred in 1960. By the end of the decade, the monument had “serious structural deficiencies.” Peace signs graffiti marred its exterior, and a circular medallion from the memorial’s floor had been stolen.

In passing decades, new national war memorials, beautiful, grandiose, and somber, drew crowds around the National Mall. Visitors and residents forgot about the local memorial that sat secluded in an overgrown segment of West Potomac Park.

Eagle on D.C. War Memorial’s north elevation. 2005. Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/Boucher)

In 2003, the D.C. Preservation League added the D.C. War Memorial to its Most Endangered Places list to “alert both the citizens of Washington and of the nation to the threat to this unique historic and cultural resource.” The League noted that the monument had lacked major repair work for more than three decades, and lamented that the memorial’s “history had been forgotten by most.”

It would seem that the memorial was doomed.

Survey photograph of the south elevation of the D.C. War Memorial. 2005. Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/Boucher)

A Veteran to the Rescue

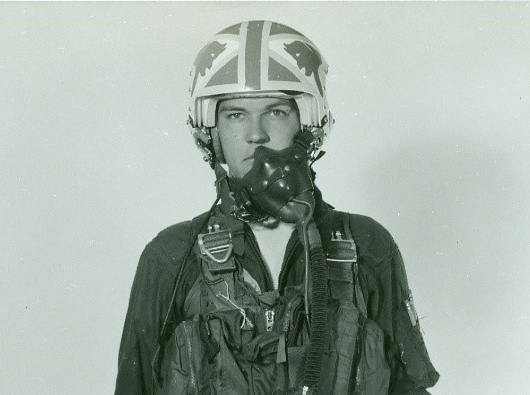

Frank Woodruff Buckles tried, and failed, on five occasions to enlist in the military before the 16-year-old convinced an Army recruiter that he was old enough to serve his country in 1917. Buckles was first sent to England, where he repeatedly requested that his superiors transfer him to France. Though he got his transfer, the youth never reached the front lines to join in the battle he longed to fight.

“Frank Woodruff Buckles, age 16, U.S. Regular Army, First Ft. Riley Casual Detachment of 102 men.” (AFC 2001/001/01070) (PH0001001) 1917. Ft. Riley, Kan. (Veterans History Project Collection, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress/photographer unknown)

Decades later, Buckles’ greatest battle would be to ensure that his fellow service members’ sacrifices were honored by the nation.

On a wintry day in 2008, the 107-year-old visited the D.C. War Memorial. From his wheelchair, Buckles noted that the memorial was in disrepair, and that the names inscribed on its sides belonged only to the District’s war dead. Because there was no national monument to the First World War in the nation’s capital, Buckles formed the National World War I Memorial Foundation with photojournalist David DeJonge. Together, they led the fight to restore the D.C. War Memorial, and have it rededicated as the national memorial for World War I.

Due to political infighting, the D.C. War Memorial would remain a local rather than a national monument, but Buckles’ efforts were not in vain. The memorial received $3.6 million in restoration funds from the American Recovery and Restoration Act in 2010.

Over the course of a year, EverGreene Architectural Arts renewed the monument’s exterior, returning the Vermont marble to its original brilliant white. The fieldstone walkway around the raised circular dome was recreated, and overgrown landscaping was cut back. The memorial’s lighting and electrical works were updated, and finally, the stolen floor medallion was replaced with a replica made of bronze.

In February 2011, while the memorial was still under construction, Buckles passed away at the age of 110.

On Nov. 10, 2011, nearly 80 years after its dedication, the District of Columbia War Memorial reopened. The memorial’s future upkeep was entrusted to the National Park Service. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in July 2014.

After politicians decided to maintain the D.C. War Memorial’s local scope, they also allowed for the construction of a new National World War I Memorial in Washington D.C.’s Pershing Park. The expensive project is currently underway. Highly stylized, filled with interpretative artwork and moving symbolism, it was designed by present-day architects to impress the heft of soldiers’ service in World War I on the individuals who stand before it.

Until the new structure is finished, the D.C. War Memorial will remain the sole monument to the heroes of World War I in the District. After the new memorial is created, the D.C. War Memorial alone will fulfill the purpose intended by those who saw the First World War. It will remain a communal space where civilians and veterans can gather together to joyfully celebrate the service and sacrifice our national heroes.

District of Columbia War Memorial. Monday, Jul. 15, 2019. Washington, D.C. (Flickr/Cutrer)

District of Columbia War Memorial. Monday, Jul. 15, 2019. Washington, D.C. (Flickr/Cutrer)

The Past Informs the Present

Veterans Brooke, Peaslee, and Wyeth created a monument that would stand long after the First World War’s veterans were gone. Buckles’ act of securing that memorial for generations to come is proof that our veterans continue to serve the nation, and their fellow veterans, long after they leave the military.

As ever, America’s history informs its present. As our post-9/11 conflicts wind down, we will begin to contemplate creating fitting local and national memorials that honor those who fought our most recent battles, and those who gave their lives in service to the nation. Our predecessors’ efforts to memorialize their history and foster joyful community between all Americans offers insight on how we modern citizens might commemorate the service of our warfighters, and our fallen, for future generations.

Want to be published in the Freedom Hill Press? Send us a pitch or a completed piece (under 2,000 words, please) to info@freedomhillcoffee.com. We can't wait to hear from you.